Guatemalan Chuchitos: The Complete Recipe & Cultural Guide

Discover The History

In the vibrant tapestry of Central American cuisine, few dishes capture the soul of Guatemala quite like the humble chuchito. These compact, corn husk-wrapped parcels represent centuries of culinary evolution—a delicious syncretism where pre-Columbian Mayan tradition meets Spanish colonial influence. Unlike their larger, banana leaf-wrapped cousins, chuchitos occupy a special place in the national consciousness as the quintessential street food, the celebration staple, and the comfort bite that connects generations.

The name itself tells a story. Chuchito derives from the Guatemalan diminutive of chucho (meaning dog), reflecting the playful, affectionate linguistic style characteristic of the region. It’s a term of endearment for a food that has earned its place at every market stall, family gathering, and Christmas feast across the country. Resources like Guatemala Food have documented how this seemingly simple antojito embodies the complexity and warmth of Guatemalan gastronomy.

What distinguishes chuchitos from other tamale varieties isn’t merely size—it’s philosophy. Where traditional tamales serve as elaborate main courses, chuchitos are democratic: accessible, portable, and meant to be shared. Their preparation, while requiring patience, rewards the cook with dozens of perfectly steamed packages that freeze beautifully and reheat effortlessly, making them as practical as they are delicious.

Historical and Cultural Foundations

The chuchito’s origins are inseparable from corn itself—the grain that Mayan mythology places at the very center of human creation. The Popol Vuh, the sacred text of the K’iche’ Maya, describes how the gods fashioned humanity from corn dough after failed attempts with mud and wood. This spiritual significance elevated corn beyond mere sustenance; it became the material of existence itself.

Pre-Columbian peoples throughout Mesoamerica developed sophisticated techniques for processing corn, including nixtamalization—the alkali treatment that transforms hard kernels into pliable masa. Wrapped preparations of seasoned corn dough existed long before European contact, though they differed significantly from modern chuchitos. These early tamales were primarily vegetarian, filled with beans, squash, chiles, and wild greens.

The Spanish conquest of the 16th century introduced pork, chicken, and beef to the indigenous culinary repertoire. This collision of food cultures produced new hybrid dishes, and the chuchito emerged as one of the most successful adaptations. The basic Mayan technique—corn masa wrapped and steamed—remained intact, but the fillings expanded dramatically to include the meats and spices brought from the Old World.

Today, chuchitos hold particular significance during Christmas celebrations, when families gather to prepare enormous batches in communal cooking sessions. The dish appears at weddings, baptisms, and saints’ day festivals, functioning as both nourishment and social glue. In markets throughout Guatemala City, Antigua, and smaller towns, vendors sell chuchitos from large covered baskets, serving them with practiced efficiency to hungry customers seeking a quick, satisfying meal.

Understanding the Chuchito: Anatomy of a Perfect Bite

At its core, a chuchito is an exercise in textural and flavor balance. The exterior corn husk serves purely as a cooking vessel and wrapper—never eaten, but essential for the steaming process that transforms raw masa into tender, cohesive dough.

The masa must achieve a specific consistency: soft enough to be moldable, firm enough to hold its shape during cooking, but never wet or sticky. Traditional recipes call for corn flour mixed with rendered lard or vegetable shortening, which contributes both flavor and the pliable texture necessary for wrapping.

The recado—the soul of the chuchito—is a thick, deeply flavored sauce built on tomatoes and dried chiles. Guatemala’s chile guaque, with its moderate heat and fruity undertones, forms the backbone of most recipes.

The meat filling, whether chicken or pork, serves as the protein anchor. Chicken pieces are typically pre-cooked through brief boiling, while pork may be incorporated raw into the recado, cooking through during the steaming process.

Regional Variations and Family Traditions

While the basic chuchito formula remains consistent across Guatemala, regional variations and family-specific adaptations create a rich diversity of expressions. In the western highlands, where indigenous Mayan communities maintain strong culinary traditions, chuchitos may feature local chile varieties and preparation techniques passed down through generations.

Coastal regions sometimes incorporate softer, more tropical flavors, while urban areas like Guatemala City have seen modern interpretations that experiment with non-traditional fillings. Some families guard secret recado recipes that include unexpected ingredients—a particular combination of spices, a splash of vinegar, or a specific roasting technique for the chiles.

The distinction between chuchitos and tamales colorados deserves particular attention. Both are beloved Guatemalan preparations, but they differ substantially. Tamales colorados are larger, wrapped in banana leaves rather than corn husks, and feature a softer, more elaborate masa that may incorporate potato or rice flour. Their fillings tend toward greater complexity, sometimes including prunes, olives, capers, and multiple types of meat. Tamales also encompass sweet varieties—tamales dulces or tamales navideños—filled with fruits, nuts, and sugar.

Chuchitos, by contrast, maintain a rustic simplicity. Their smaller size, drier masa, and straightforward filling make them the everyday choice, the market snack, the casual accompaniment to coffee or atol (a warm corn-based beverage). This accessibility has cemented their place as perhaps the most frequently consumed tamale variety in the country.

Essential Ingredients and Components

For the Masa (Dough)

The foundation of any chuchito begins with quality corn flour. Instant corn flour, such as Maseca brand, has become the standard for home preparation, offering consistency and convenience. Traditional preparation would involve grinding nixtamalized corn, but this labor-intensive process has largely given way to commercial flour in contemporary kitchens.

Core masa ingredients include:

- Corn flour (harina de maíz): 2–3 cups for a standard batch

- Melted vegetable shortening or lard: Approximately ½ cup, providing richness and pliability

- Vegetable oil: 2–3 tablespoons for additional moisture

- Chicken bouillon (consomé de pollo): 1–2 teaspoons for seasoning depth

- Salt: To taste, typically 1 teaspoon

- Warm water: Added gradually until proper consistency is achieved

The fat component merits special consideration. Traditional recipes call for rendered pork lard (manteca de cerdo), which delivers incomparable flavor and texture. Vegetable shortening provides a similar mechanical function—creating tender, cohesive masa—but with a more neutral taste. Some cooks use a combination, balancing tradition with dietary preferences.

For the Recado (Sauce)

The recado distinguishes Guatemalan chuchitos from tamale preparations elsewhere in Latin America. This thick, concentrated sauce infuses the filling with complex, layered flavors.

Standard recado ingredients:

- Tomatoes: 6–8 large, ripe tomatoes form the base

- Chile guaque: 4–6 dried chiles, seeds removed

- Chile sambo (optional): 2–3 for additional heat and flavor

- Miltomates (tomatillos): 4–5 for brightness (optional but traditional)

- Onion: 1 medium, quartered

- Garlic: 4–6 cloves

- Cumin powder: 1 teaspoon

- Salt and black pepper: To taste

- Vegetable oil: For frying

- Sugar: A pinch to balance tomato acidity

For the Filling

- Chicken: 1–1.5 pounds, cut into small pieces, or

- Pork: 1–1.5 pounds, cut into bite-sized cubes

- Additional chicken bouillon: For seasoning the cooked meat

For Wrapping

- Dried corn husks (hojas de mazorca/tusa): 30–40 husks for a standard batch

- Strips of corn husk or kitchen twine: For tying

Step-by-Step Preparation Guide

Day Before: Preparing the Recado and Meat

Experienced cooks recommend preparing the recado one day in advance. This not only saves time on assembly day but allows the flavors to meld and deepen overnight.

Step 1: Remove stems and seeds from the dried chiles. Rinse briefly to remove dust. In a dry skillet over medium heat, toast the chiles for 2–3 minutes per side until fragrant and slightly darkened. Do not burn—this creates bitterness.

Step 2: Place toasted chiles in a bowl, cover with hot water, and soak for 20–30 minutes until softened.

Step 3: Meanwhile, roast tomatoes, miltomates (if using), onion quarters, and garlic cloves. This can be done under a broiler, on a comal (griddle), or in a dry cast-iron skillet. Roast until charred in spots and softened throughout, approximately 15–20 minutes.

Step 4: Combine softened chiles, roasted vegetables, cumin, salt, pepper, and a pinch of sugar in a blender. Process until smooth. For a silkier texture, strain through a fine-mesh sieve, pressing to extract all liquid.

Step 5: Heat vegetable oil in a large saucepan over medium-high heat. Carefully pour in the blended sauce (it will splatter) and fry, stirring frequently, for 10–15 minutes until thickened and darkened slightly.

Step 6: If using chicken, boil pieces in salted water with a teaspoon of chicken bouillon for 10–12 minutes until cooked through. Drain and set aside. If using pork, it can be added raw to the cooled recado.

Step 7: Once the recado has cooled to room temperature, fold in the meat pieces. Cover and refrigerate overnight.

Assembly Day: Preparing Husks and Masa

Step 8: Early in the day, prepare the corn husks. Separate individual husks, discarding any that are torn or too small. Rinse under running water to remove dust and debris. Place in a large container, cover with hot water, and weight down with a plate to keep submerged. Soak for at least 3–4 hours, or overnight, until completely pliable.

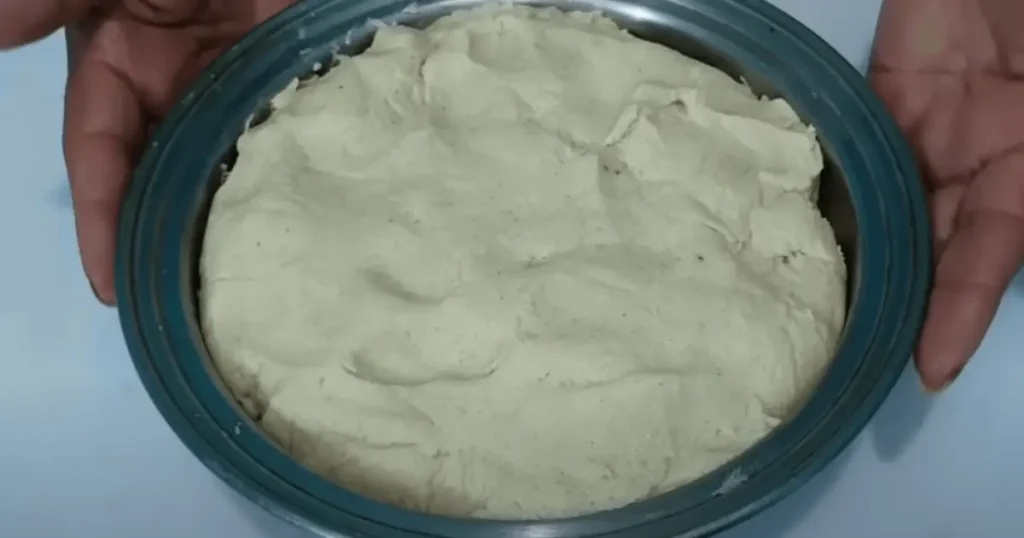

Step 9: Prepare the masa. In a large mixing bowl, combine corn flour with melted shortening. Use your hands to work the fat into the flour until the mixture resembles coarse crumbs.

Step 10: Dissolve chicken bouillon and salt in warm water. Add to the flour mixture gradually, mixing and kneading continuously. The goal is a smooth, pliable dough that holds together when squeezed but doesn’t stick excessively to your hands. Adjust with additional water or flour as needed.

Step 11: Cover the prepared masa with a damp cloth to prevent drying while you work.

Assembly

Step 12: Drain the corn husks and pat dry with clean towels. Select the largest, most intact husks for wrapping. Tear a few husks into thin strips for tying.

Step 13: Lay a husk flat on your work surface, with the wider end facing you. Take a portion of masa approximately the size of a golf ball (about 2 tablespoons) and place it in the center of the husk.

Step 14: Using your fingers or the back of a spoon, flatten the masa into an oval shape, approximately ¼ inch thick, leaving at least 1 inch of husk border on all sides.

Step 15: Create a small indentation in the center of the flattened masa. Place one or two pieces of meat and a generous teaspoon of recado into the indentation.

Step 16: Carefully fold the masa over the filling, using the husk to help shape it. The goal is to completely enclose the filling within the masa.

Step 17: Fold the sides of the husk over the masa, then fold the narrow (top) end down toward the filled portion. The wider (bottom) end remains open or is folded under.

Step 18: Secure the chuchito by tying a strip of corn husk or kitchen twine around the middle. This helps maintain shape during cooking.

Step 19: Repeat until all masa and filling are used. A standard batch yields 25–35 chuchitos.

Cooking

Step 20: Prepare a large pot or steamer. If using a regular pot, place a steaming rack, inverted plate, or crumpled aluminum foil in the bottom to elevate the chuchitos above the water line.

Step 21: Add water to the pot—enough to generate steam but not touching the rack. Approximately 2–3 inches is typical.

Step 22: Arrange chuchitos vertically in the pot, open end facing up, leaning against each other for support. Pack them snugly but not too tightly.

Step 23: Cover with a layer of extra corn husks, then a clean kitchen towel, then the pot lid. The towel absorbs condensation that would otherwise drip onto the chuchitos.

Step 24: Bring water to a boil over high heat, then reduce to medium-low. Steam for 60–90 minutes. The chuchitos are done when the masa is firm, cooked through, and separates easily from the husk without sticking.

Step 25: Remove from heat and allow to rest for 10 minutes before serving. This resting period helps the masa set.

Expert Tips and Common Mistakes to Avoid

Masa Consistency Is Everything. The most common failure point in chuchito preparation is incorrect masa texture. Too wet, and the dough won’t hold its shape; too dry, and the finished product will be crumbly and dense.

Don’t Skip the Husk Soaking. Impatient cooks sometimes abbreviate the soaking time, resulting in brittle husks that crack during wrapping. The minimum soaking time is three hours; overnight is preferable. Properly soaked husks should feel supple and almost leathery, bending without cracking.

Toast, Don’t Burn, Your Chiles. The line between perfectly toasted and burnt chiles is thin. Burnt chiles introduce an acrid, bitter note that permeates the entire recado. Toast over medium heat, watching carefully, and remove at the first sign of darkening. The chiles should be fragrant and slightly flexible, not blackened or crispy.

Balance Your Recado Acidity. A small pinch of sugar in the tomato sauce makes a significant difference. Tomatoes’ natural acidity can overwhelm the other flavors; sugar doesn’t make the sauce sweet but rounds and balances the profile.

Maintain Water Level During Steaming. Over the 60–90 minute cooking time, water will evaporate. Check periodically and add hot (not cold) water as needed to maintain steam generation. Running dry not only stops cooking but can scorch the pot bottom.

Let Chuchitos Rest Before Serving. The temptation to eat immediately is strong, but allowing 10 minutes of resting time helps the masa firm up and makes unwrapping much easier.

When Freezing, Go Cooked. While technically possible to freeze raw chuchitos, cooked ones freeze and reheat far more successfully. Raw corn masa tends to crumble after thawing, compromising texture and appearance.

The Science Behind the Steam

The transformation of raw masa into the tender, cohesive interior of a finished chuchito involves several simultaneous processes. Understanding these mechanisms helps explain why specific techniques matter.

Starch Gelatinization: Corn flour contains approximately 70% starch, primarily in the form of amylose and amylopectin. When heated in the presence of moisture (provided by the masa’s water content and the steam environment), these starch molecules absorb water, swell, and eventually rupture, releasing their contents. This gelatinization process—which begins around 150°F (65°C) and completes by 200°F (93°C)—transforms the gritty raw flour into a smooth, cohesive gel.

Protein Denaturation: Corn contains relatively little protein compared to wheat, but the proteins present (zeins) do contribute to structure. Heat causes these proteins to unfold and cross-link, forming a network that helps the masa hold together.

The Role of the Husk: The corn husk wrapper isn’t merely a convenient package—it’s functionally important. It creates a contained environment where steam can penetrate evenly, it prevents direct contact with condensation that would make the exterior soggy, and it allows some moisture exchange that keeps the masa properly hydrated without becoming waterlogged.

Traditional Recipe

The chuchito stands as a testament to Guatemala’s culinary heritage—a dish that has sustained families for centuries while adapting to changing circumstances and tastes. Its preparation demands patience and attention but rewards the cook with dozens of individually wrapped treasures that freeze beautifully, reheat effortlessly, and bring authentic Central American flavor to any table.

Mastering chuchitos means understanding the interplay of simple components: the neutral canvas of properly prepared masa, the deeply savory punch of well-made recado, the satisfaction of meat that has absorbed hours of slow-cooked flavor. It means respecting techniques refined over generations—the proper soaking of corn husks, the precise consistency of dough, the careful balance of a tomato-based sauce that neither overwhelms nor disappears.

Whether you’re preparing chuchitos for the first time or refining a technique learned from grandparents, the process offers both practical satisfaction and cultural participation. These small, corn husk-wrapped packages carry centuries of history in every bite—a legacy worth preserving, sharing, and celebrating.